The Holocaust: What Grandpa Saw

Grandpa filmed the joy of the liberation of the Holysov Concentration Camp in Czechoslovakia. The women in the striped uniforms in the clip below are Jews from Belgium and France, slave labor finally freed in May, 1945. Grandpa arrived at the Holysov camp as they were liberated.

My grandfather's ability to speak Czech was his passport into a wide range of adventures in the last week of the war. The US Army desperately needed translators as they liberated Southern Czechoslovakia, and Czech was grandpa's first language. What had made him odd within his division -- the only officer whose native tongue was Czech -- suddenly made him quite valuable.

Above, grandpa looks like a rooster in a hen house as the freed female prisoners crowd around him, vying for his attention. He also wrote that the women in the Czech towns he helped liberate kissed and hugged him. I chuckle at the thought of my grandpa as a George-Clooney-in-combat-boots, but apparently it happened.

Holysov was one of 80 sub-camps of the Flossenburg Concentration Camp in Germany. Over 30,000 people died in the Flossenburg camps. I visited both Holysov and Flossenburg with my guide and dear friend, Amar Ibrahim, on my recent research trip.

Holysov Camp guard tower

Crematorium, Flossenburg Camp

The final weeks of the war, Flossenburg's crematorium burned all-day to keep pace with the Nazi's accelerated kill-rate. As Allied troops approached, the SS officers running Flossenburg evacuated many of the prisoners in a death march toward the Dachau concentration camp outside of Munich, 140 miles away. My grandfather unexpectedly discovered dead bodies and escapees from the Flossenburg death march as he and his driver crossed alone into Czechoslovakia on the morning of May 2, 1945. He wrote:

As we drove along I began to notice dead bodies on the right and left of the highway. This puzzled me as I knew of no battles in this area. I noticed they all wore the same uniform, all were above apparent military age, and all shot through the head; some with one and some with two bullet holes.

Flossenburg death march fatality

FlosLt. Colonel Matt Konop

He continues:

After a few stops to take pictures, my driver called my attention to some men coming down a hill from the woods, waving their hands. I asked them (in Czech) who they were and what they were doing in this area. They told me that they were escapees from a column of thousands being moved from concentration camps in Germany and that the tail end of that column passed the point we were at not more than fifteen minutes ago. Three days before, the inmates of the camp were told to assemble to move out of the camps. With little food and water the prisoners were formed as a road march unit and, guarded by SS German prison guards who road vehicles, put on the road. Their marches were mostly during the night as they did not want to be spotted by American airplanes during the day.

I asked them about those dead along the road and how they happened to be shot. They told me that these dead were members of the prison camps and march unit. They said that the gruesome march in the warm spring days caused many to fall out only to be shot as the German SS came upon them as he road in his car.

They said that when a man became exhausted and about to fall, his buddies on the right and left of him would take the exhausted under their arms and just about carry him until all three became exhausted and all three fell out of formation on the road and then all three were shot and dumped in the ditch. This explained to me why I saw a single body here and there and then again I saw three in one pile dead.

My grandfather got the men food and water. They took him to a building of about 100 other escapees, many sick and dying in front of him. He noticed dogs in the building and asked why they kept dogs if they had no food for themselves.

This scene was a pathetic one and I was helpless. The answer I got was unexpected; they said they ate the dogs. I noticed a little dog and went over to pet him, much to the delight of the many in the camp. This little dog was picked up along the road and carried as he was too small to walk too far. They told me they were saving this special pet for the day they would have to eat him as a last resort after all other dog meat was gone. Now that I came there, they told me that I saved his life. I arranged to have farmers get whatever potatoes, beets, or bread and bring it to the se people along with water. I asked two medics to get medical supplies to the escapees. I bid goodbye and proceeded to the next village, Klenci.

From that horror scene, my grandfather and his driver entered Klenci, coincidentally the home village of his grandmother, Mary Hruska (my great great grandmother). While snooping around town he stumbled upon a meeting of the Klenci resistance. As he walked into their secret meeting, the men were surprised to see an America officer, and then shocked when he spoke Czech. When he told them in Czech they were now free the men burst into joy, hugging and kissing him. They also marveled at the good fortune to be, as they said, "liberated by one of our own," as all four of grandpa's grandparents had immigrated to America from this little area of Czechoslovakia. The men made him a folk hero, less than an hour after he had left the hell scene of the dog meat.

Grandpa never spoke of the death march, but he did yell at anyone in his house who threw away food. I learned that the hard way. He did write about his experiences, including what is quoted above. He also filmed the liberation of the Holysov Concentration Camp, and the disturbing scene below of German citizens forced to exhume dead bodies in shallow graves outside the Czech town of Volary. A column of the Flossenburg death march passed through Volary and the dead were just piled in a mass grave. They were like the fallen death marchers my grandfather found after crossing into Czechoslovakia. I wonder what my grandfather thought as he filmed it, bodies like the ones he saw as he crossed into the land of his grandparents.

I knew my grandfather well and was a pallbearer at his funeral in 1983. But it has only been in the last two years that I've discovered what I've written about here. In fact, up until a few years ago I did not include the Holocaust in my show, The Accidental Hero, because I wasn't certain if grandpa's description was accurate. I needed proof. I discovered the movie clips two years ago in a canister of film that sat unwatched in my aunt Jean's basement for decades. Then my Czech friend Amar Ibrahim unlocked for the meaning of the clips for me. I had my proof and changed the show.

On my recent trip to the Czech Republic Amar took me to the Flossenburg Concentration Camp. His grandfather, Arnost Hruska, had been imprisoned in Flossenburg during the war.

The Nazis rounded up Arnost and 150 other men from Domazlice, Czechoslovakia in 1940 and threw them into Flossenburg in retribution for the resistance activities of a local native, Jan Smudek. Arnost Hruska was a successful businessman in Domazlice, his stately building on the main square sits just five doors down from City Hall. The Nazis made an example of him, a display that no Czech regardless of position in life was safe. Lucky to survive hard labor in the Flossenburg granite quarry and the daily presence of death, Arnost returned to his family weighing eighty pounds.

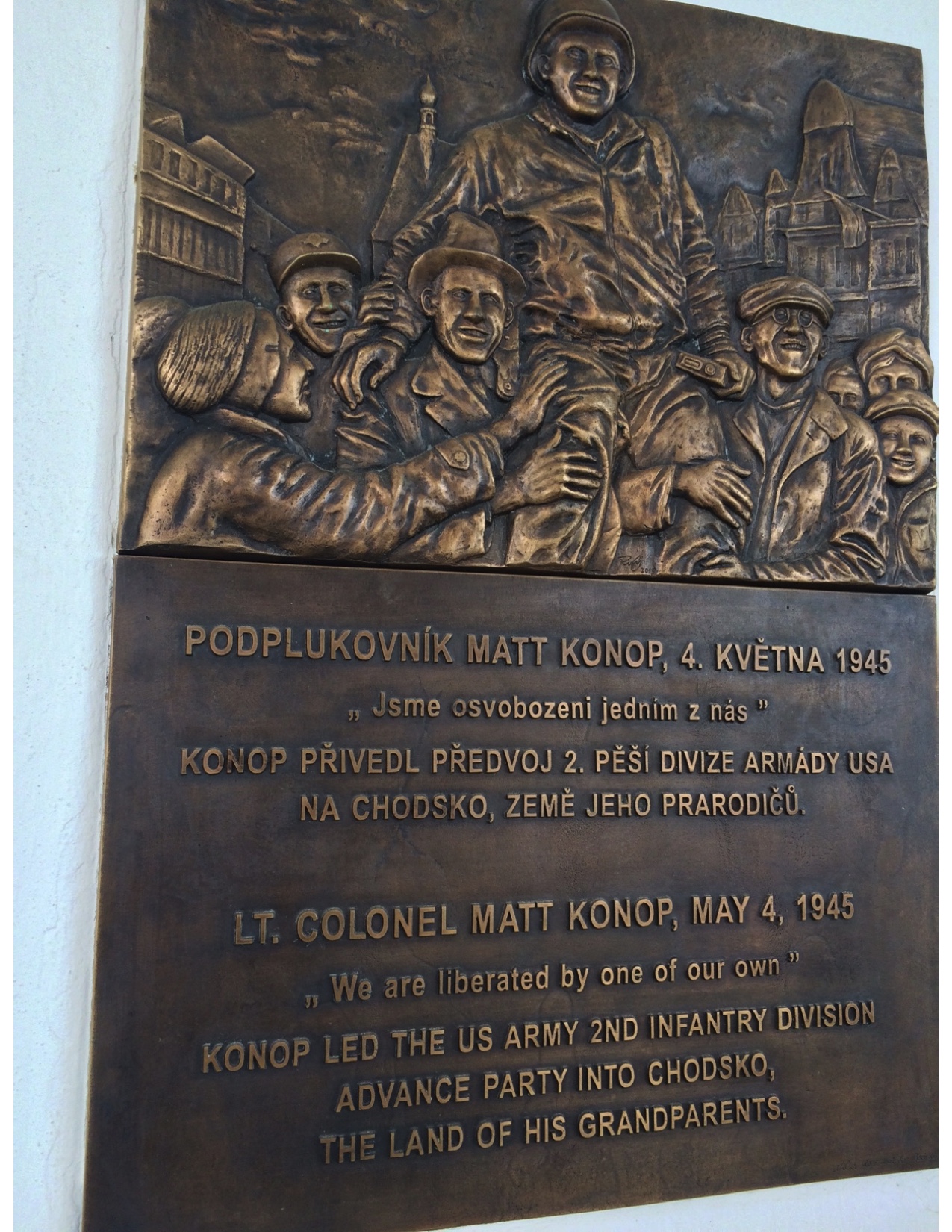

Today, Arnost Hruska's white and salmon building on the main square sports a bronze plaque dedicated to my grandfather. Grandpa had parked his jeep in front of Arnost's building on May 4, 1945, his first visit to Domazlice. Grandpa looked up and saw his grandmother's name, Hruska, on the side of the building. Now my grandfather's name is on the side of that building, along with a bronze relief of him being carried as a hero by the people of Domazlice.

Plaque in Domazlice, Czech Republic

Amar Ibrahim and his daughter with me in front the plaque of my grandfather, Lt. Col. Matt Konop.

Amar and I are good friends. He lives in the Hruska building where he keeps a museum to my grandfather on the second floor. If you visit Domazlice he'd be happy to show it to you.

These war stories are personal. Amar's grandfather and family were victims of the Nazi terror reign, while my grandfather's story has connected me to my Czech roots. On the train ride from Domazlice back to Prague after spending a few days with Amar, I re-read my grandfather's writings. I discovered, with the Czech scenery passing by the train window, that our grandfather's had met. Yes, these stories are personal, often terrible, and sometimes magical.

I managed to drive to Klenci and Domazlice to see what I could discover as to my forefathers. The first place I stopped in Domazlice was the Hruska building where I met Arnost Hruska, operator of a general store.

Matt Konop carried in the main square of Domazlice, Czechoslovakia on May 4, 1945. The photo was taken a few meters from Arnost Hruska's building. Note the movie camera in my grandfather's left hand.

Jewish Monument, Flossenburg

Hruska Building, Domazlice Main Square